News

Africa Lost \$90 Billion Annually to Imported Substandard Fuel — Dangote

By Ohworisi Elohor

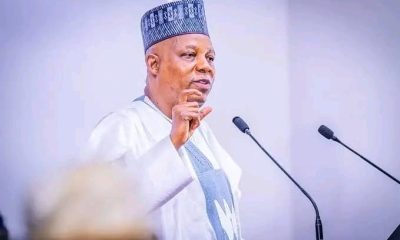

Africa was reported to have become a major destination for cheap and often toxic petroleum products, many of which were blended to substandard levels that would not be permitted in Europe or North America. This concern was raised by the President and Chief Executive of Dangote Industries Limited, Aliko Dangote, during the West African Refined Fuel Conference held in Abuja.

The event was organized by the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority (NMDPRA) in partnership with S\&P Global Commodity Insights.

It was revealed by Dangote that due to limited domestic refining capacity, Africa imported over 120 million tonnes of refined petroleum products annually, costing approximately \$90 billion. While acknowledging the Nigerian National Petroleum Company Limited (NNPC) for supplying some cargoes of Nigerian crude since production began, it was disclosed that monthly imports of crude oil from the United States and other countries ranged between 9 to 10 million barrels.

Despite producing around 7 million barrels of crude oil per day, only about 40% of Africa’s daily consumption of 4.3 million barrels of refined products was refined locally. This stood in stark contrast to Europe and Asia, where over 95% of refined products consumed were produced domestically.

Dangote emphasized that while the continent produced significant crude oil volumes, it continued to import refined products, thereby exporting jobs and importing poverty. He highlighted that the \$90 billion market opportunity was being captured by regions with surplus refining capacity. To illustrate this, it was pointed out that only around 15% of African countries had a GDP greater than \$90 billion, meaning the continent’s economic potential was being handed over to others annually.

While reaffirming belief in free markets and international cooperation, Dangote stressed that trade should be grounded in economic efficiency and comparative advantage without compromising quality or safety standards. He remarked that it was illogical for Africa to export raw crude only to re-import refined products that could be produced closer to both source and consumption.

Reflecting on the experience of constructing the world’s largest single-train refinery, Dangote outlined numerous technical, commercial, and contextual challenges unique to the African environment. The Dangote Petroleum Refinery was described as one of the most capital-intensive and logistically complex industrial projects ever undertaken, requiring extensive land clearing, site stabilization, and massive infrastructure development.

At the project’s peak, over 67,000 personnel, including 50,000 Nigerians, were engaged, coordinating across multiple disciplines and nationalities. The COVID-19 pandemic caused a two-year delay, adding further complexity and risk to the project.

The refinery’s construction also necessitated the creation of a dedicated seaport, as existing Nigerian ports could not accommodate the volume and size of equipment needed. This involved handling over 2,500 heavy equipment pieces, 330 cranes, and establishing the world’s largest granite quarry, with an annual production capacity of 10 million tonnes.

Despite the refinery’s technical achievements, significant commercial challenges were encountered. Exchange rates deteriorated sharply from N156/\$ at inception to N1,600/\$ upon completion, and crude oil sourcing remained problematic. Instead of purchasing crude directly from Nigerian producers at competitive terms, negotiations had to be conducted with international trading companies, which purchased Nigerian crude and resold it with high premiums.

Logistical and regulatory bottlenecks also contributed to increased costs. Port and regulatory charges accounted for up to 40% of total freight costs, sometimes amounting to two-thirds of vessel chartering expenses. It was noted that refiners in India, who sourced crude from farther away, enjoyed lower freight costs due to the absence of excessive port charges faced in West Africa.

Furthermore, it was revealed that loading domestic petroleum cargoes from the Dangote Refinery was more expensive than from competing ports such as Lomé, as customers were charged both at loading and discharge points, whereas Lomé customers paid only at discharge.

The lack of harmonized fuel standards across African nations was also criticized, as it created artificial barriers to regional trade. Fuel produced for Nigeria could not be sold in neighboring countries like Cameroon, Ghana, or Togo, despite similar vehicle standards. This fragmentation benefited international traders who profited from market arbitrage, while local refiners suffered inefficiencies.

One example cited was Nigeria’s diesel cloud point standard set at 4 degrees Celsius, which limited the types of crude that could be processed and added costs. Other African countries had more flexible ranges between 7 and 12 degrees, indicating potential regulatory adjustments that could ease refining operations.

Dangote also raised concerns about the increasing influx of discounted, low-quality fuel, often originating from Russia and blended with crude under price caps, being dumped in African markets.

In closing, a call was made for African governments to implement protective measures for domestic refiners, following the examples set by the United States, Canada, and the European Union.